Ensuring Equitable Access to Needed Care for the Seriously Ill through the Medicare Care Choices Model (MCCM)

By:

Lori Bishop, MHA, BSN, RN, NHPCO Vice President of Palliative & Advanced Care

Annie Acs, MPH, NHPCO Director of Health Policy & Innovation

Dianne Munevar, MPP, Senior Director, Health Care Strategy, NORC at the University of Chicago

Ryan Murphy, MPH, Data Scientist, Health Care Evaluation, NORC at the University of Chicago

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed gaps in traditional health care, particularly how we care for our most vulnerable and seriously ill patients. More than a year into the pandemic, we now have data on the disproportionate devastation wrought upon racial and ethnic minority groups across our country. A new report from the CDC found that, “provisional life expectancy at birth [for the total population] in the first half of 2020 was the lowest level since 2006.” This drop in life expectancy differed across races – the life expectancy for the non-Hispanic black population “declined the most, and was the lowest estimate seen since 2001”.

For a seriously ill individual, having the option to stay home to receive health care could save their life. However, most health care services are still delivered mainly in the hospital or in physician office settings. And given the workforce shortages across our nation’s hospitals and most health care settings, which are extreme in some underserved communities, this has meant certain patient populations simply do not get the care they need.

One often underutilized solution to this problem is community-based palliative care. Beneficial at any stage of a serious illness, palliative care is an interdisciplinary model of care designed to anticipate, prevent, and manage physical, psychological, social, and spiritual suffering to optimize quality of life for patients, their families and caregivers. Care is delivered by hospice and palliative care providers through an interdisciplinary team in the patient’s home, allowing those already suffering from serious illness to remain safe from communicable disease, comfortable, and surrounded by loved ones while alleviating the burden on our nation’s hospitals, many of which are stretched to capacity due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

The National Hospice & Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) and the National Coalition for Hospice & Palliative Care propose adding coverage of community-based palliative care to a second generation of the Medicare Care Choices Model (MCCM), a successful Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) demonstration. This would provide a path to testing a new option for eligible Medicare beneficiaries to receive palliative care services from selected hospice providers, while continuing to receive services provided by other Medicare providers, including care for their terminal condition. A second-generation MCCM would be open to hospice and other providers that provide palliative care to improve the quality of care for at-risk individuals, reduce the occurrence of preventable hospitalizations and emergency department visits, deploy limited workforce more effectively, and enhance the use of telehealth and lower total costs of care for the seriously ill. Expanding MCCM to allow for pre-hospice community-based palliative care may help to address current racial and ethnic disparities.

It should be noted that a growing number of private insurers offer community-based palliative care benefits across business lines, including Medicare Advantage (MA). However, there is no benefit for traditional Medicare enrollees to access these services, it cannot be delivered using the traditional Medicare fee schedule and billing rules, and the lack of defined minimum services and standard quality measures for palliative care within MA results in inadequate care for many beneficiaries.

NHPCO partnered with NORC at the University of Chicago (“NORC”) to evaluate the potential that a second-generation MCCM or community-based palliative care (CBPC) could have on improving care for the seriously ill, while better managing costs of care. NORC analyzed Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS) beneficiaries with serious illnesses like Alzheimer’s, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), and Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) between 2016-2018 and found that upwards of 2.5 million beneficiaries who died during this period may have benefitted from a CBPC model, such as the one described above.

In their last two years of life, this medically complex population has an average health services utilization and costs of care almost 4.5 times higher than the average Medicare FFS beneficiary, highlighting an opportunity to improve end-of-life care. For example, between 2016 and 2018, this seriously ill population experienced an average 3.6 hospitalizations and approximately six emergency department (ED) visits in their last two years of life, with average costs of care over $59,000, per beneficiary.

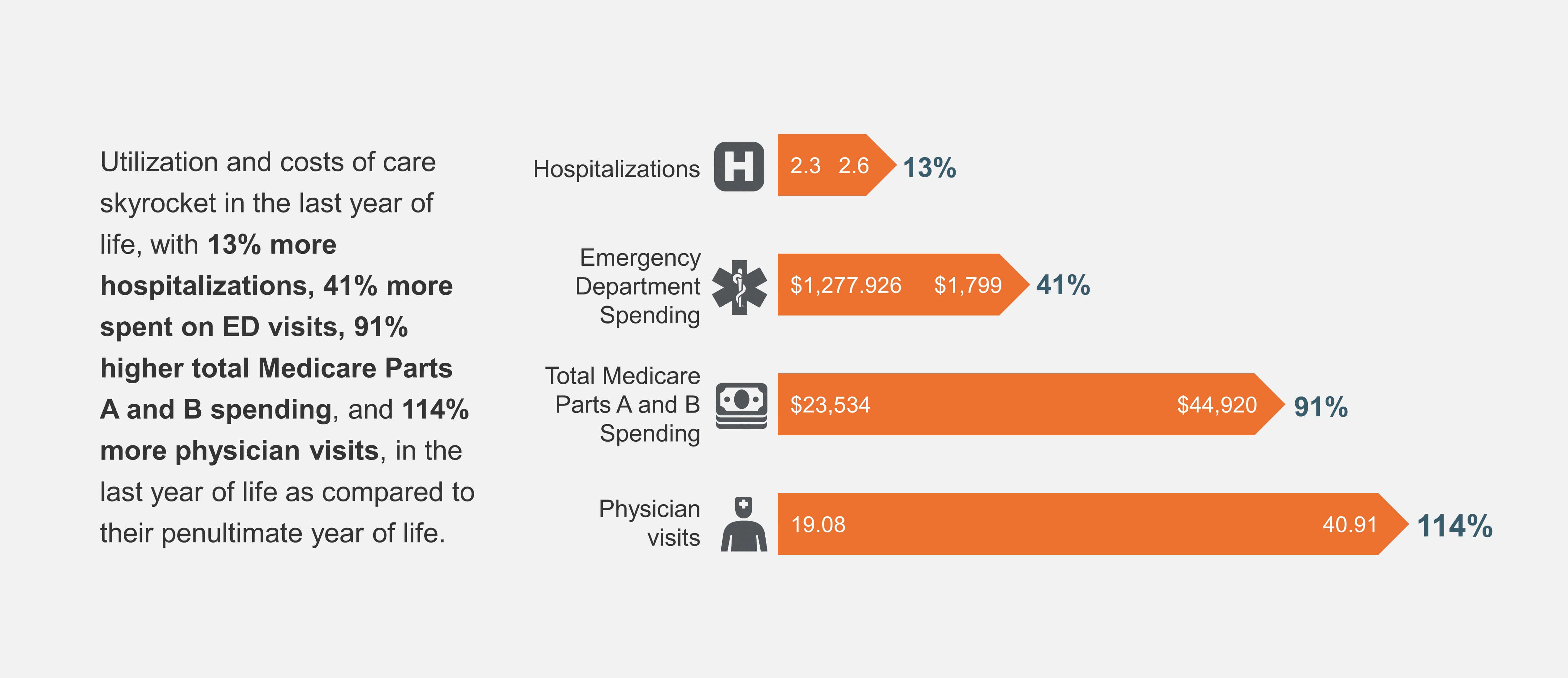

What is more astounding is how utilization and costs of care skyrocket in the last year of life, with 13% more hospitalizations,114% more physician visits, 41% more spent on ED visits, and 91% higher total spending in the last year of life as compared to their penultimate year of life.

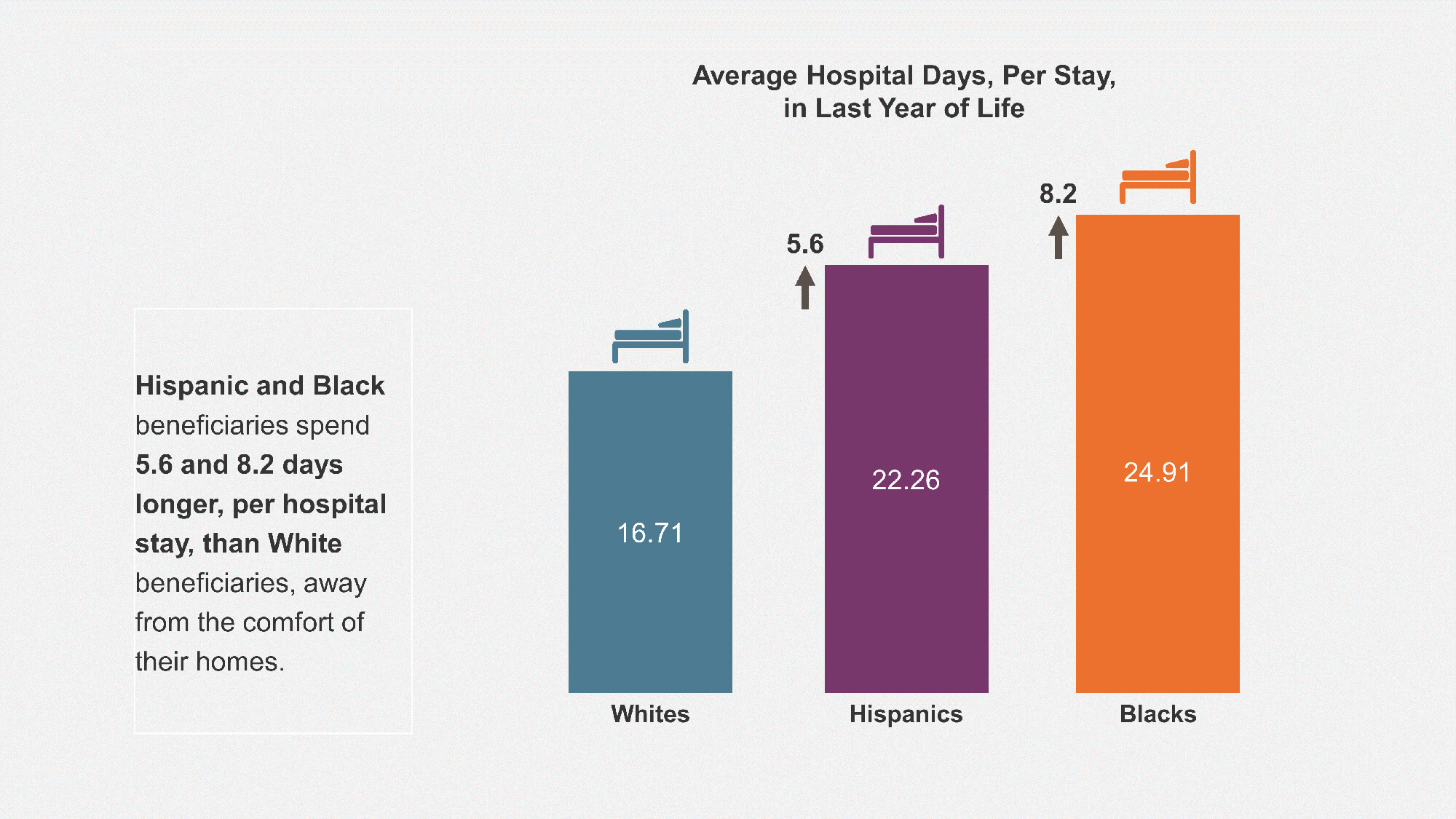

The findings for last year of life are even more dramatic for Black and Hispanic beneficiaries, and for dual-eligible beneficiaries. On average, Black beneficiaries had 25% more hospitalizations, and longer hospital stays relative to program-eligible White beneficiaries – that is 8.2 more days per stay spent away from the comfort of their home. Black beneficiaries also visited their physicians 34% more in their final year of life than their White counterparts.

Hispanic beneficiaries share a similar disparity with 19% more hospitalizations, 5.6 more days per stay spent hospitalized, and 21% more physician visits in their last year of life relative to program-eligible White beneficiaries.

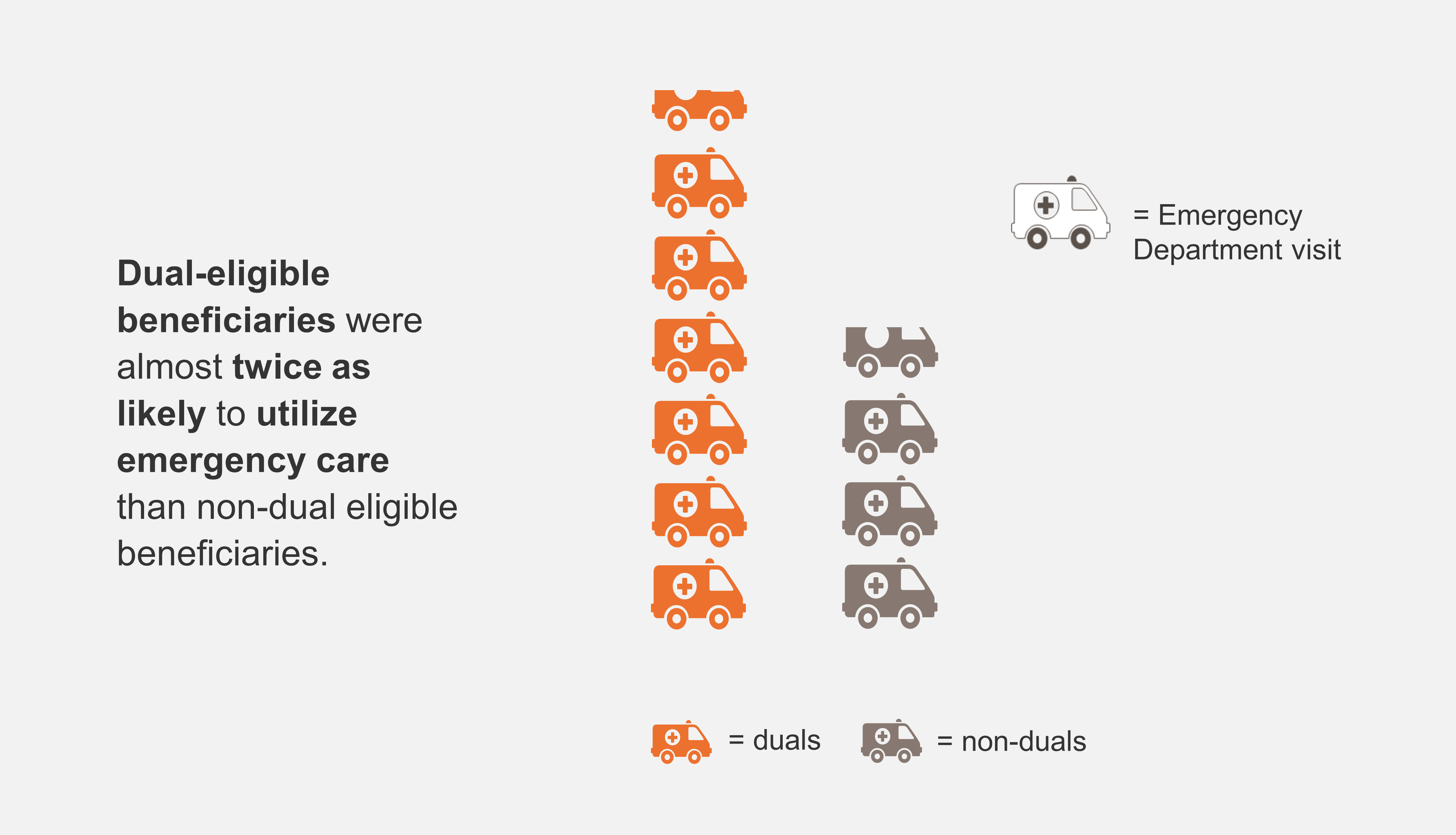

Dual-eligible beneficiaries also experience dramatic differences in care utilization and spending in their last year of life. Dual-eligible beneficiaries were almost twice as likely to utilize emergency care and ambulance services, 6.6 versus 3.8 visits, respectively, and were hospitalized 15% more than non-dual eligible beneficiaries.

The NORC analysis leveraged the findings from Medicare Care Choices Model (MCCM) and other innovative Medicare programs and research studies to estimate the potential savings of a community-based palliative care model.

NORC’s analysis of the potential savings of a community-based palliative care model included assumptions about physician referral rates and clinical appropriateness of the model, as well as patient enrollment rates. Following evidence-based assumptions of recruitment and participation, per similar CMMI demonstrations, NORC estimates that an enhanced community-based palliative care model could see initial enrollment of about 117,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries in the first year and 126,000 by year two. With an additional monthly payment to participating CBPC entities of $600 per member, and a 20% program efficacy rate, the estimated Per Member Per Month (PMPM) for Medicare FFS savings is approximately $143 in year one and $179 in year two.

These favorable reductions in Medicare FFS spending align with findings from the most recent report for the MCCM, published in October 2020, which found a 25% decrease in total Medicare expenditures amounting to $21.5 million in net savings from January 2016 through September 2019.

Expanding the current MCCM to cover more conditions and more beneficiaries, and increasing the monthly payments to qualifying entities from $400 to $600 PMPM, can provide more equitable care in a home-based setting to those with complex, chronic illnesses. Additionally, by testing a benefit that removes key barriers to care for some seriously ill individuals, we believe that there will be an increase in access to palliative care for underserved populations.

Currently, hospice is limited to patients with less than six months to live and requires that both the patient and the family acknowledge impending death, “a concept that often runs counter” to the spiritual beliefs of people of color.

Replacing the “or” with “and” in the choice between the hospice benefit and curative treatment restores a sense of dignity to those beneficiaries with a terminal illness. CMMI must act now to ensure that vulnerable and seriously ill individuals gain access to care that is person-centered, equitable, and cost-effective.

References

1 Arias, E., Tejada-Vera, B., & Ahmad, F. (2021). Provisional Life Expectancy Estimates for January through June, 2020.

2Average total costs of care include all hospital, post-acute, DME, physician services, Part B drug, and ambulance claims. The estimate does not include Part D drugs.

3Abt Associates (2020). Evaluation of the Medicare Care Choices Model – Annual Report 3.

4Brumley MD, R. e. (2007). Increased Satisfaction with Care and Lower Costs; Lustbader MP FAAHPM, D., & al., e. (2017). The Impact of a Home-Based Palliative Care Program; Yosick, L. (2019). Effects of a Population Health Community-Based Palliative Care Program on Cost and Utilization; Abt Associates (2020) Evaluation of the Oncology Care Model: Performance Periods.

5Yancu, C. N., Farmer, D. F., & Leahman, D. (2010). Barriers to Hospice Use and Palliative Care Services Use by African American Adults. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®, 27(4), 248–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909109349942

Bibliography

Arias, E., Tejada-Vera, B., & Ahmad, F. (2021). Provisional Life Expectancy Estimates for January through June, 2020 . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/VSRR10-508.pdf.

Associates, A. (2020). Evaluation of the Medicare Care Choices Model – Annual Report 3. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Associates, A. (2020). Evaluation of the Oncology Care Model: Performance Periods 1-3. Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Brumley MD, R. e. (2007). Increased Satisfaction with Care and Lower Costs: Results of a. JAGS, 993-1000.

Lustbader MP FAAHPM, D., & al., e. (2017). The Impact of a Home-Based Palliative Care Program. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 23-27.

Yancu, C. N. (2010). Barriers to Hospice Use and Palliative Care Services Use by African American Adults. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®, 27(4), 248–253.Yosick, L. (2019). Effects of a Population Health Community-Based Palliative Care Program on Cost and Utilization. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 1075-1081.