Specialized COVID-19 Unit Reunites Patients, Families

Some Louisiana families whose loved ones are dying from COVID-19 have found solace in a specialized hospice unit that is caring for patients infected with the virus.

Heart of Hospice Inc. opened its inpatient COVID-19 unit on April 15 in Metairie, a suburb of New Orleans. The company, headquartered in Charleston, S.C., with locations in five states, is one of several hospices across the country opening or converting inpatient facilities to serve COVID-19 patients.

In hospitals and other acute-care settings, patients with the virus are isolated, with visitors banned to lower the risk of new infections. Those dying from COVID-19 are often alone or surrounded by strangers, a heartbreaking scenario for patients, families, and bedside clinicians.

Offering another option has been a priority for hospices that have the resources and abilities to make it happen. Specialized COVID-19 hospice units have been a godsend for patients nearing death and their families.

“I’m a nurse, and I’ve done a lot of hands-on hospice care,” said Melissa Moody, RN, CHPN, who directs Heart of Hospice’s COVID-19 unit in Metairie. “I have to say this is the best thing I have ever done professionally.”

Ramping Up Quickly

The unit started as a farfetched idea by Heart of Hospice’s leadership team in response to demand from other providers, said Brandon Melancon, RN, Regional Vice President of Operations for Heart of Hospice.

New Orleans was a known COVID-19 hot spot. There had been 26,000-plus cases reported for the state through April 25, and few long-term care facilities were taking patients who were infected. Many with the virus who were already frail, elderly, or seriously ill with pre-existing disease faced death in the hospital. Providers were looking for alternatives.

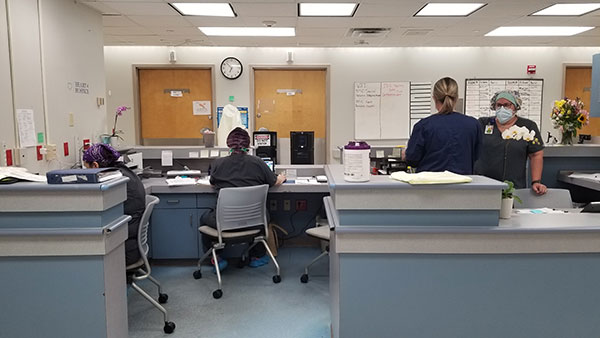

Heart of Hospice learned a lease was freeing up on a 15-bed unit at East Jefferson Hospital in Metairie and approached the State Department of Health and Hospitals with a proposal to turn the space into a specialized COVID-19 hospice unit.

Officials there indicated they had “been hoping somebody would step up,” Melancon said. The hospice worked quickly to obtain temporary licensure, good through June 30.

Staffing the unit was one of the biggest issues, but the company put out a call and got 36 volunteers from its various sites, Melancon said. Moody, the unit director, came from Arkansas.

Within two weeks, the company completed all the necessary infrastructure and training to open. That included securing enough personal protective equipment (PPE) for staff and for families who visit, implementing strict cleaning and infection-control protocols.

“As we were putting things on the shelves, I was doing a virtual site visit with the state,” Moody said.

‘Ministry of Presence’

The unit admitted 28 COVID-19 patients in its first 10 days. What is taking place there has been difficult but incredibly meaningful for patients, families, and staff.

“In hospice we refer to it as ‘the ministry of presence,’ ” Moody said. “Most people would rather die at home. The next best thing is to have people from home come to them, so they don’t die with strangers.”

“We admitted a patient yesterday whose family hadn’t seen them since December,” she added. “It’s really special, the reunions that happen. Even non-responsive patients respond.”

Not all family members are able to visit, she said. In those cases, the hospice team uses telemedicine to connect patients with loved ones.

Comfort Measures in COVID-19

Ventilators have been widely used in hospitals for the sickest COVID-19 patients whose lung function is deteriorating, but outcomes are typically very poor. At least one recent study showed a mortality rate of roughly 88% for COVID-19 patients placed on ventilators.

The Metairie COVID-19 unit cannot admit patients who are still on ventilators because the process of removing a patient from a ventilator creates a heightened risk of infection.

Instead, the hospice uses other comfort measures to manage lung symptoms, including high flow oxygen support with nasal cannula, opioids to help patients breathe, and positioning.

“We haven’t seen a lot of secretions in these patients,” Moody said. “It’s like a dry pneumonia.”

The unit is staffed at a higher level than a typical acute-care hospital and has an interdisciplinary team of RNs, CNAs, and a social worker and chaplain who visit every day to provide spiritual and psychosocial support.

That support is integral to the work hospices do every day.

“This crisis is horrible. And yet, it is also our time as professionals to show our mettle,” National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization President and CEO Edo Bamach said in an April 3 call to action published on the NHPCO website.

“I thank all those in the hospice and palliative care community for your work and commitment to the people we care for. It is our time to step up, to lean in, and to be as large as this moment.”